Problems with Leasehold Flats

Leasehold tenure, as a form of residential property ownership, is in the view of many property professionals, lawyers and politicians, archaic, exploitative and unnecessary.

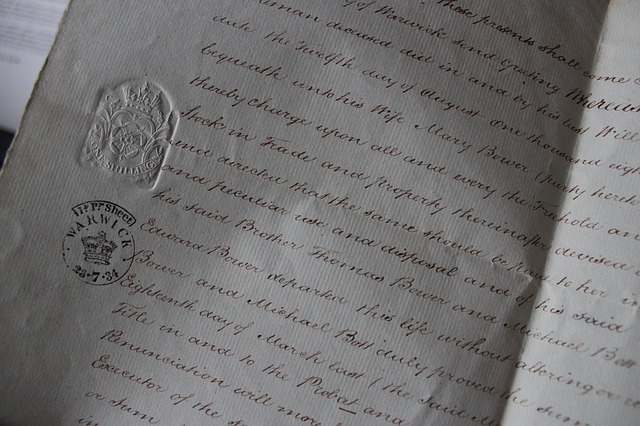

The system of leasehold property ownership is a relic of feudal law dating back to the 11th Century, when land ownership was synonymous with power and status. A complex system of land ownership known as subinfeudation existed, with absolute ownership of all land vested in the Crown, and a pyramid system of tenures below. Land was granted in return for rent, military service, religious service or personal service, each of which created a different kind of tenure. At the bottom of the pyramid landowners granted serfs the right to work on a plot of land for a fixed period of time in return for a portion of the profits generated by that land. The feudal system because increasingly complicated, until it was largely abolished by the statute of Quia Emptores in 1290.

In the early 1900s as much 90% of housing in England was privately rented, with tenants paying a ‘market rent’ and enjoying little security of tenure (much as is the case today). The introduction of the various Rent Acts in the early 20th Century held down rent levels and made evicting tenants much more difficult. Consequently being a landlord became a less attractive business. Landlords began to sell long leases, typically of between 60 and 99 years, in order to release the latent value of their property without losing absolute ownership of the land. Thus began the modern system of leasehold property ownership as it exists today.

During the 1950s the system of leasehold property ownership grew exponentially with the construction of a growing number of flats. Flat ownership involves a number of complexities, such as the right of support from flats below, and the need for numerous owners to contribute to the maintenance of their shared building. These complexities were easily addressed by the leasehold tenure system, which allows for the creation of both positive and negative contract terms (called covenants) which are enforceable not only on the original lessee, but also any subsequent owners of the lease.

Problems with Leasehold Flats

However, there are a number of problems with leasehold flats. In the first place, it must be noted that the lessee is, in fact, still a tenant of the property, rather than its outright owner. When the lease comes to an end so will the leaseholder’s right to occupy the property (provisions of the Local Government and Housing Act 1989 notwithstanding). Freehold owners will, where permitted by the leases, seek to use their responsibility for maintenance of the building alongside other matters to generate management fees. Under most leases an annual rent is reserved (called ground rent), which can amount to a significant amount of money.

Over the last 50 years Government has sought to remedy a number of the issues associated with leasehold property ownership. In 1967 the Leasehold Reform Act gave owners of leasehold houses the right to purchase extended leases or acquire their freeholds. The Landlord and Tenant Act 1987 made provisions for leaseholders to compulsorily acquire their landlord's interest in cases where the landlord is in serious breach of his obligations, and gave leaseholders the right to ‘first refusal' when their freeholder’s interest was sold. The Leasehold Reform, Housing and Urban Development Act 1993 gave leaseholders the right to collectively purchase their freehold, or to individually purchase extended leases.

Despite the reams of statutory intervention leasehold property ownership is still complex and fraught with difficulties. Leaseholders are all too often hit with high service charges and management fees from unscrupulous freeholders and managing agents. Refusal to pay can open the door to the freeholder taking the nuclear option of forfeiting the lease. Permission to alter leasehold property often requires the freeholder’s consent, and in some cases, prohibitive premiums will be levied.

When leaseholders enact their statutory rights to extend their leases or buy their freeholds they will often be met with resistance from the freeholder, who may demand an exorbitant premium, leaving the leaseholder with no option but to accept and overpay or incur the significant costs associated with having the case determined by the Residential Property Judiciary. The added ‘kick in the teeth’ is that in all but the most extreme cases, and even in the event of an unqualified ‘win’, costs of a valuation tribunal hearing will not be recoverable.

The frustration of those professionals representing leaseholders in this sector (not to mention politicians, such as Sir Peter Bottomley, who has made it a personal mission to rout out and expose the failings of the sector) is conflated by the fact that there is a perfectly viable alternative. The Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act 2002 introduced commonhold as a new system of freehold tenure for units within multi-occupancy buildings, but with shared responsibility for common services, based on the success of similar systems in the America, Australia and Canada.

However, uptake of the system has been disappointing, with only a handful of commonhold schemes created since the Act was passed. Most homeowners will never have heard of commonhold, and whilst flat buyers are content to purchase long leases, there is little incentive for developers to offer anything else. In the absence of increased in public awareness of statutory intervention, this issues associated with the ownership of leasehold property seem set to endure.

|

Dakota Murphey achieved a BA (Hons) degree in marketing and business. She now spends her time working as an independent content writer for a number of property specialists including leasehold property experts, Peter Barry. |

<< Back to Property Investment Blueprint from Problems with Leasehold Flats

<< Back to Guest Posts from Problems with Leasehold Flats